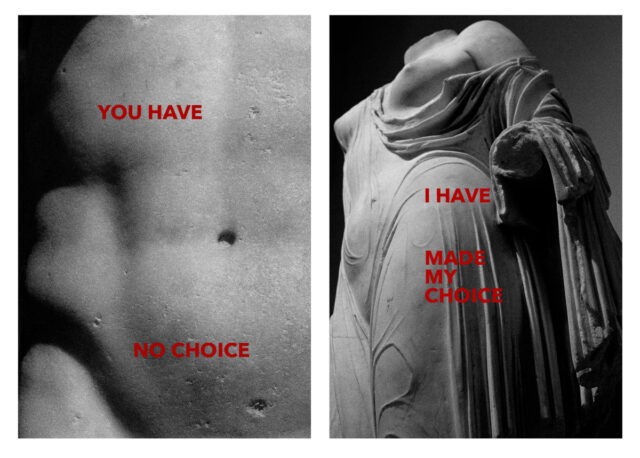

Andrea Eis (American, b. 1952)

Antigone and Kreon

47 x 32.5 in

Diptych, archival pigment prints on cotton rag mounted on aluminum

Gift of Van Hillard, Davidson College Professor of Rhetoric and Writing Emeritus

The torso is the true abode of the mind. That is, according to the Ancient Greeks; (φρήν/phrḗn) may be translated as “mind, resolve, will, heart” and refers anatomically to the abdomen. On the left, Kreon’s abdomen resembles the kind of stone-faced masonry meant to fortify cities—and fortification was precisely the concern of this king of Thebes in the Sophoklean tragedy Antigone. The contention between the two characters above, Kreon and Antigone, canonically follows the tragedy Oedipus the King (though it was written over a decade later). When Oedipus was King, he falsely accused his cousin, Kreon, of attempting to steal the kingship. It was Kreon who served as the voice of reason then, cringing at the prospect of being king himself.

But Kreon, in the end, assumed the kingship and banished Oedipus on charges of patricide and incest. When Oedipus’ sons Eteokles and Polynikes vied for the Theban throne, each killed the other. His two daughters, Antigone and Ismene, were his only legacy. Kreon fell into power by default. The following years bore witness to the slow lithification of Kreon’s mind (φρήν/phrḗn). He ensured that his nephew Eteokles was buried with military honors, but deemed Polynikes an enemy of the state, unworthy of burial entirely—and whoever did bury the body of Polynikes would be subject to death by stoning.

When Kreon’s stone-cold patriotism seemed most indestructable, Antigone made the choice to bury Polynikes, defying one who is both a tyrant and a parental figure. In fact, translators of the eponymous heroine’s name suggest either “in place of one’s family (sacrificial)” or “against one’s family”. The Greek prefix ἀντί can mean either, but I prefer to understand her name as meaning both.

Andrea Eis distills the drama into nine grave words: YOU HAVE NO CHOICE; I HAVE MADE MY CHOICE

Her retelling simulates the effect of a literary fragment, somehow more full by its thinness. The artifact (the drama itself) predates us by 2,500 years, but Andrea draws out and preserves its still-living marrow with a sense of urgency. Sophokles’ Antigone has been adapted to film, song, and stage for good reason: sincere meditation on the human experience. One may empathize with Antigone’s duty to piety or with Kreon’s enslavement to fear. The story may conjure feelings of longing for something universal (justice, gender equality, religious freedom) or for something personal (familial reconciliation, closeness, a voice).

Antigone and Kreon is part of a series of photographic-collages, featuring more of Andrea’s retellings. One diptych, entitled The Oracle of Delphi, features the words: SHE SPOKE HER MIND; THEY HEARD HIS. Another called Euridice Rising says, “doubting, he turned to her; knowing, she took the chance”. To see more, check out her website! All of her work engages with language and story (a feature I find altogether irresistable).

Andrea Eis is an artist working in film, photography and works on fabric. She earned her BA in Classics and Anthropology from Beloit College, her BFA in Film, Photography, and Video from Minneapolis College of Art and Design, and her MFA in Photography from Cranbrook Academy of Art (1982). Her work has been exhibited in solo exhibitions at numerous venues including Grace Teshima Gallery, Paris, France; International Center for Hellenic and Mediterranean Studies, Athens, Greece; and Sweet Briar College, Sweet Briar, VA. Other recent exhibitions include MAMU Gallery, Budapest, Hungary; North Branch Project, Chicago, IL; Target Gallery, Torpedo Factory Art Center, Alexandria, VA; University of Detroit Mercy, Detroit, MI; and University of Windsor, Windsor, Canada. She has been the recipient of many grants and awards including a Minneapolis College of Art and Design Artist-in-Residence Grant; National Endowment for the Arts Art in Public Places Grant; National Art Education Foundation Grant; Michigan Council for the Arts Creative Artist Grants; and, Doris and Paul Travis Endowed Professorship in Art, Oakland University (2007). She is currently a Distinguished Professor of Film Studies and Production at Oakland University in Rochester, MI.

Antigone and Kreon is currently on view on the first floor of Chambers Academic Building.

– Molly Smith ’24