Art by Alumni

Homecoming

Van Every / Smith Galleries

On View: October 12, 2023— December 06, 2023

Opening Reception: November 2, 2023, 5:30 pm— 7:30 pm

Related Programs & Events

Gallery Talk with Alumni Artists

November 1, 2023, 4:30 pm—5:30 pm

Career Connections

November 2, 2023, 11:05 am—12:05 pm

Friends of the Arts Reception

November 2, 2023, 5:30 pm—7:30 pm

In celebration of the thirtieth anniversary of Davidson College’s Katherine and Tom Belk Visual Arts Center, the Van Every/Smith Galleries and the Department of Art are embarking on a year-long reflection aimed at honoring our past and the folks who helped shape our community, as well as imagining our future impact on the visual arts on campus and regionally.

As part of this significant occasion, the Van Every/Smith Galleries are pleased to present Homecoming: Art by Alumni, a group exhibition highlighting diverse visual art practices of nine accomplished artists. The exhibition recognizes each alum’s individual explorations while also highlighting a common thread: an emphasis on the visibility and physicality of the artist’s hand. Drawing on practices that rely on seeking, selecting, composing, arranging, and manipulating, the works presented—photographs, sculptures, paintings, digital art, and mixed-media works—evoke a tangible connection to and deep reliance on process and materials in support of each artist’s unique conceptual ideas.

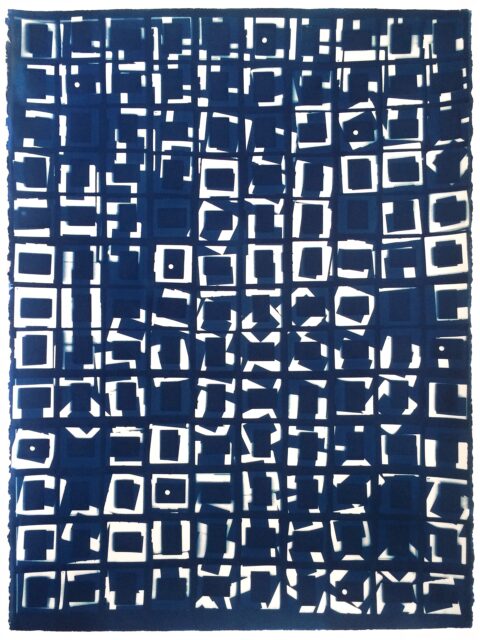

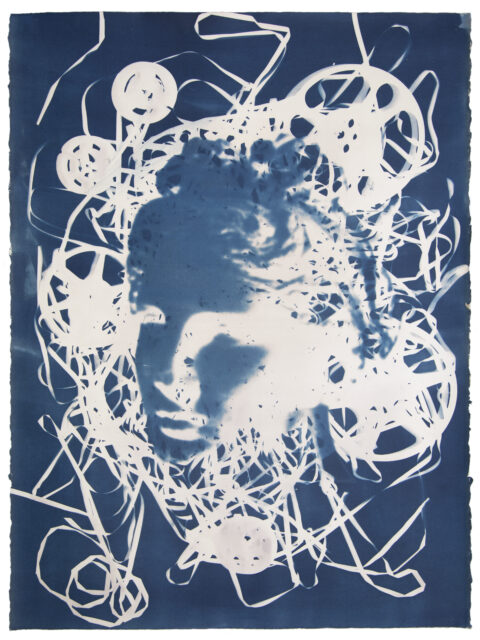

Elijah Gowin’s cyanotypes depict materials that would have been prevalent in the lecture hall and seminar room when the Belk Visual Arts Center first opened its doors in 1993. At many institutions, including Davidson College, the content on old film reels and slides has been digitized, and the equipment associated with these materials has largely become obsolete. Gowin’s images merge his concept and process; he creates photographic images of outdated teaching tools through an analog, cameraless process using only emulsion-coated paper, light, and objects.

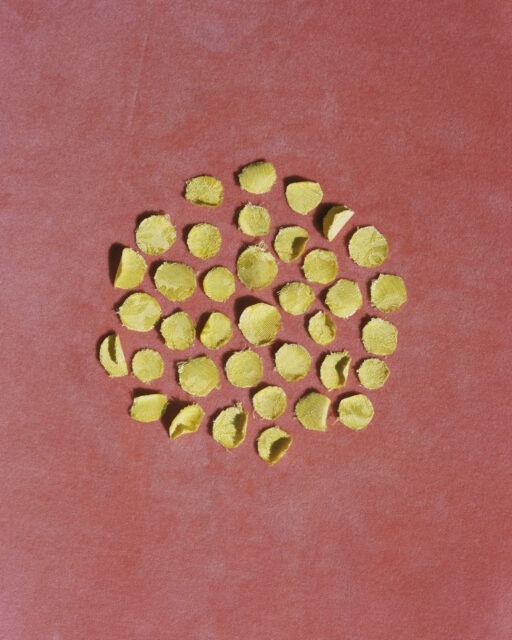

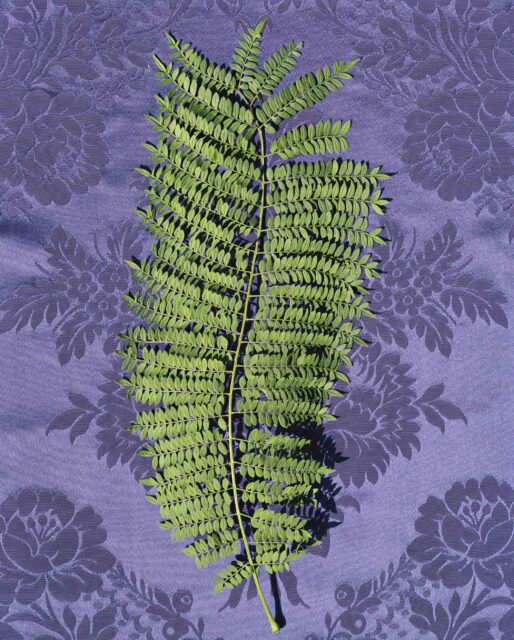

Like Gowin, Malú Alvarez is also creating carefully composed still life photographs, but in her case using a large-format film camera. Her current work merges past memories of her Mexican homeland and ancestral ties to Spain with her recent spiritual pilgrimages to India. Alvarez’s close observation, careful collection of materials such as woven textiles and sand from the Sahara desert, and her meticulous arrangement of such objects, are particularly evident in such works as Ganges (Earth, Sun, Moon, Water), Sahara I, and Gold Petals I. Alvarez documents her compositions in an effort to remember the essence of a place—and herself—at a particular moment in time.

Taylor O. Thomas also attempts to understand time, space, and the body, but through gestural painting on canvas. Her large-scale abstractions illuminate the process of making. For example, the movement of Thomas’s shoulder and arm is visible in the large swaths of blue that dominate An Unfinished Phrase. But on closer inspection, one notices a much more intimate, controlled gesture: that of the artist’s deliberate hand as she incised text into the surface of the same artwork. Shifting between small and large brushes, and using an array of soft and hard implements, Thomas combines additive and reductive techniques to create works that are beautifully balanced, both smooth and highly textured, intuitive and technical, loose and tight, dark and luminous.

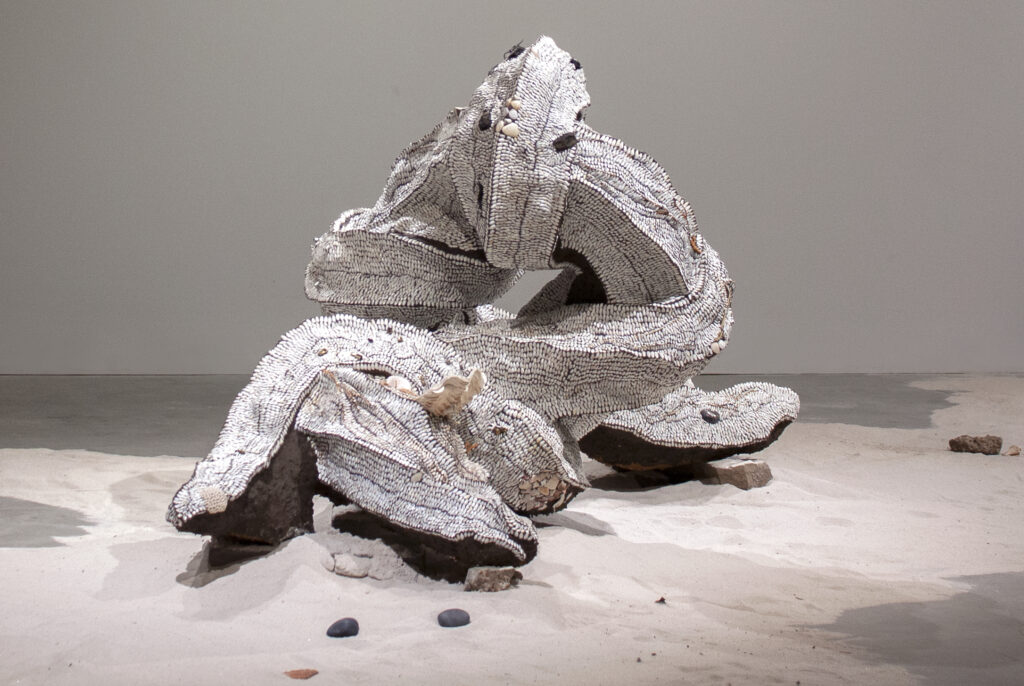

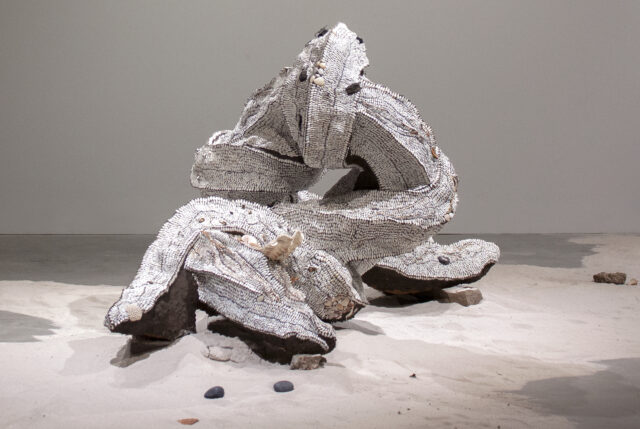

Sarah Elizabeth Cornejo creates artwork that reflects her own identity as a Peruvian American raised in the Southern US, while also speaking to larger, global environmental concerns. Snakes or serpents, central both to pre-Columbian mythology and Southern folklore, have become a recent focus of Cornejo’s sculptural installations. Amaru references the amaruca or amaru, an Incan mythological double-headed (sometimes winged) serpent believed to dwell deep in the earth or the ocean and to possess both protective and destructive powers in service of restoring earthly equilibrium. Cornejo’s seven-foot long amaru is encrusted with natural and human-made materials, including coquina and abalone shells, found bullet casings, seaweed, sea horses, and other discarded objects. One can envision the amaru, awakened by an imbalance or disturbance, emerging from deep in the earth’s core. Breaking the surface of the ocean, covered in objects that have been buried, the amaru manifests as a devastating event on earth; restoring equilibrium often comes at the expense of humanity. Cornejo’s accompanying black rubber, hand-stitched tondos hang on nearby walls. The deep black pieces draw one in, like portals, while in Our Nightmarish Pieces, rings of concentric eyes push the focus back out onto the viewer.

For decades, Susan Norman McAlister’s work has been rooted in her love of the land. Her new multicanvas composition brings together mainstays of her process—walking the land, plein air sketching and painting, and the collection of artifacts—which are then refined, collaged, and reimagined in the studio. Layers of paint, ink, graphite, and cut paper are combined to mimic the patterns, lines, and forms of foliage, light, and shadows one might experience during a walk through the landscape, particularly in the South, where McAlister resides. Her intention with Passage is not to recreate a realistic landscape but rather to evoke the feeling and emotion of time and place.

Annie Broderick identified as a painter until just six years ago, when she developed a passion for Olympic-style weightlifting. Understanding the power of her own body inspired her to consider weight and materials in a new way, and she began experimenting with textiles. She was interested in the way fabric had a relationship to the body and clothing, but more importantly, her ability to transform a woven two-dimensional cloth into a voluminous, textured dimensional sculpture. Works on view depict her interest in contrasts: soft versus hard, light versus dark, taut versus loose.

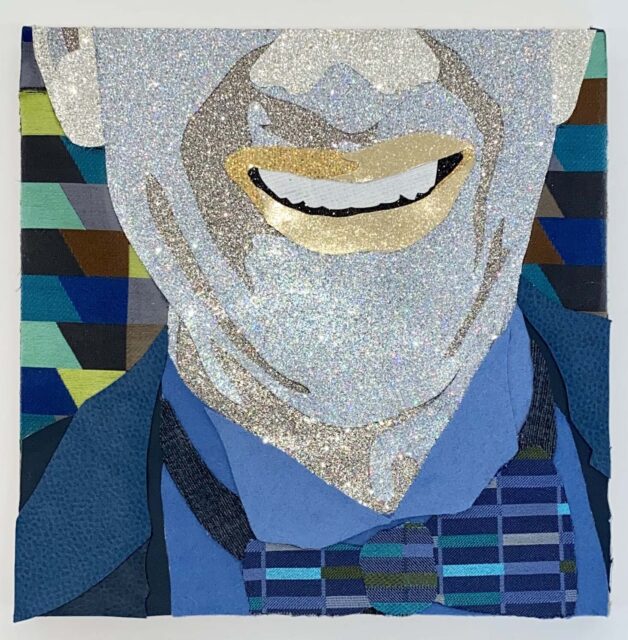

Textiles also make an appearance in Stuart Robertson’s work, along with aluminum, paint, and other collaged materials. Through his use of varied, often colorful or patterned fabric, he intends to “complicate the concept of skin color as race.” In a series of ten square works varying in size from 12 to 36 inches on a side, Robertson presents portraits of friends or family members, each titled with the sitter’s first name and last initial. In each portrait, the sitter smiles widely, their joy emphasized by bright colors and patterns, as well as glitter. The additional four paintings in the exhibition depict cropped areas of male torsos atop brightly colored backgrounds. Aluminum sheeting defines and highlights areas of the bodies. In this series, intentional cropping of the figures creates ambiguity; for example, are the figures embracing in affection, or are they grappling?

Ambiguity also plays a role in Claire Chambless’s sculptural installation. The tableau includes four components: propped-up walls and risers that make up a “set”; a sculptural object; a “conceptual-artwork-text”; and an audio piece. The sculpture, Broken Sculpture (Escape Route Module No. 10), is suggestive of an otherworldly beast’s skeleton, split into three parts. Chambless refers to the scene as “the aftermath,”but we can only imagine what occurred that resulted in such destruction. Chambless’s intention is to engage multiple senses by encouraging viewers to study the sculpture while listening to the audio, Sonic Instructions for an Escape Route, and reading her text, Notes on a Ghost Complex. The result is one of disorientation. While the three elements reference each other, something is not quite right. The text alludes to an artwork not presented here. For the sound piece, Chambless provides a set of instructions for how one would escape from inside the sculpture. Her voice has been altered and layered; it reverberates as though she is speaking from deep inside a cavernous space. Her voice normalizes toward the end of the audio; perhaps she has found her way.

Lucy Corwin is interested in the body, more specifically, the female body. While traditionally the “male gaze” refers to the sexualization of female bodies by men, Corwin focuses on the way women look at—and scrutinize—other women. Emulating high fashion editorials, Corwin’s work begins as photo shoots focused mostly on the adornment of the body—clothing, accessories, jewelry, fingernails, etc. Using Photoshop, Corwin obscures the images further, creating what she refers to as “a kaleidoscope of jewels, skin, and fabric.” She then creates photorealistic paintings from the digital images. Her new installation for the Van Every/Smith Galleries turns one of her digitally manipulated images into a wallpaper backdrop on which digital GIFs are displayed. Related paintings are hung nearby. Through such installations, the female body is framed as decorative, while the never-ending GIF loops remind us of the constant barrage of images of “perfection” and the pressure women face to maintain their appearance, particularly as they age.

Homecoming: Art by Alumni is an example of the incredible, diverse work being produced by just a small sampling of the talented artists who have passed through Davidson College. We are delighted to share these works with you and so grateful to the artists for their dedication to this project. As you read more about the artists and their work, note that the text was written by gallery interns Isabel Smith ’24 and Gaby Sanclimenti ’25—a testament to the fine work of current Davidson College students. Thanks to both Isabel and Gaby, as well as Toshaani Goel ‘24, and all of our other gallery interns. Thanks also to Russ White ‘04, Marisa Pascucci, Gallery and Collection Coordinator; and David Sackett, Department Technician. The exhibition and related events are made possible through the support of the Herb Jackson and Laura Grosch Gallery Endowment and Davidson College Friends of the Arts.

—Lia Rose Newman, Director/Curator

View the exhibition brochure here: