Two weeks ago, Elizabeth Harry (gallery and collection coordinator) and I had the privilege to meet with Aubrey Parks ’22 and Dr. Dan Boye, a physics professor here at Davidson, to participate in a presentation on volumetric x-ray imaging with Digitome software. The Van Every/Smith Galleries have consulted with the physics department a handful of times over the years to examine artworks, such as this painting by Frank Vincent DuMond. This time, we examined Untitled (Village on Lake), Continental School to verify suspected old repairs or in-painting and to potentially reveal an underpainting.

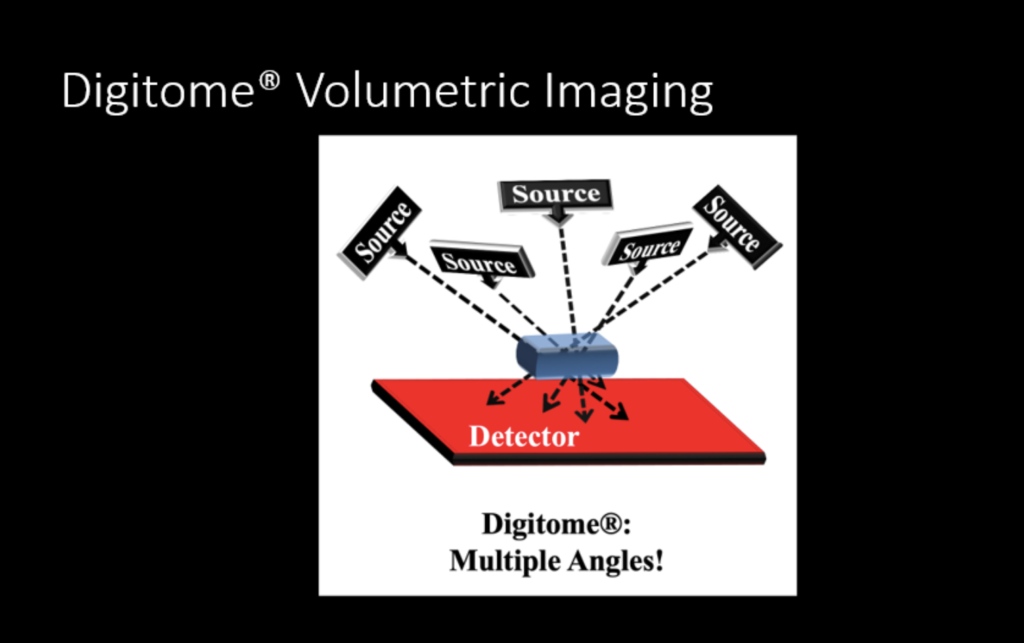

The Davidson physics department has a state-of-the-art technology, called Digitome, a volumetric X-ray imaging software that allows several images to be taken of an object from a plurality of angles to allow a better reconstruction of an X-rayed image. Because Digitome is a type of software system, the technology can be portable as long as the museum using it has proper radiation safety procedures and a portable X-ray source. This means that examinations of art and artifacts can happen directly in the museum setting.

Compared to conventional 2D radiographs, Digitome imaging shows a high level of detail. The arrangement of several scans taken at various angles creates a 3D image. With Digitome software, we can single out a thin cross-section of the object under examination. Dr. Boye and his students have brought this technology to image objects in the the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art as well as remnants of the Queen Anne’s Revenge, the infamous ship captained by the pirate Blackbeard.

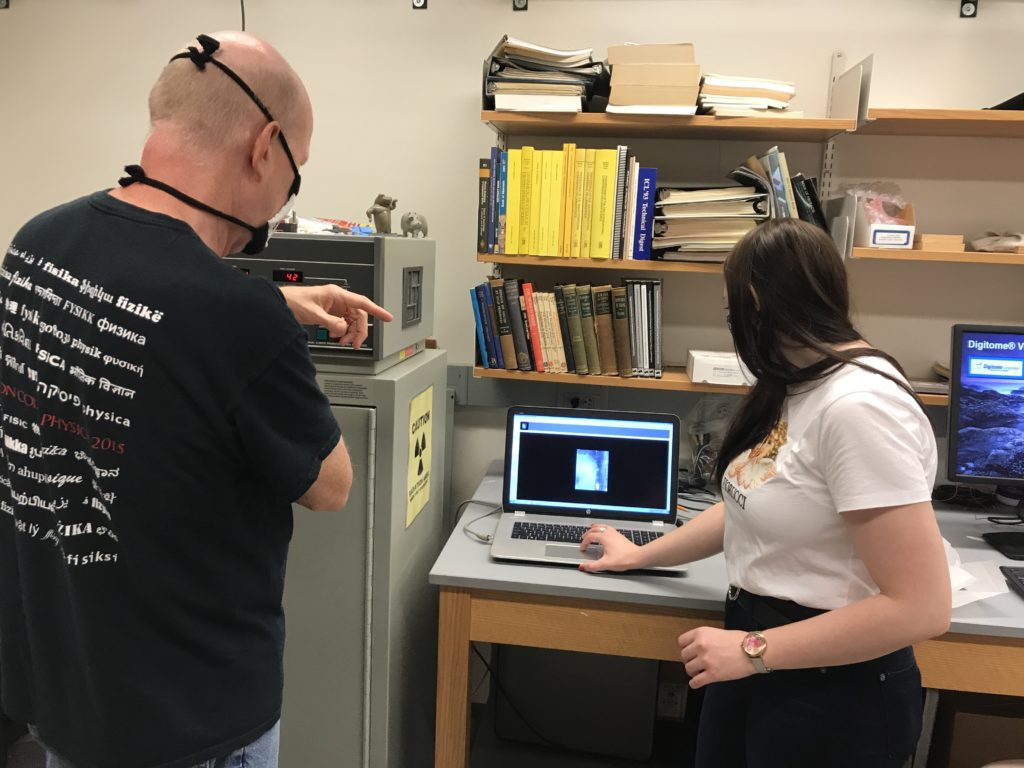

After an informational presentation, the four of us moved down to the basement of Dana Science Laboratory to watch the Digitome in action. After calibrating the X-ray machine by taking a dark and light image without the painting, Elizabeth carefully lowered Untitled (Village on Lake), Continental School onto the digital radio panel. This is a quick process– within seconds the image was ready.

The original scan revealed dark black areas between the surface of the painting and the wood, which could be cavities or areas filled with organic material.

Most notable in the scanned image above are the outlines of the buildings, the bushes along the bottom, and some places where there seems to be previous repairs. Aubrey, a physics major, mentioned that this process allows her to take something conventional in fields of science, such as digital x-raying, and apply it to a completely different, seemingly unrelated field such as art.

If you’re interested in learning more about the science of art conservation, check out this conversation with Ginny Newell ’78:

Gabi Sarussi ’21