This past fall semester, Psychology professor Dr. Greta Munger brought her General Psychology (PSY 101) students to visit the exhibition From Pandemic to Protests in the Van Every Gallery. Dr. Munger hoped this visit might provide inspiration for one of three “culture points” she prompted students to write throughout the semester. The aim of these short essays was to have students explore the relationship between Psychology and the arts. Dr. Munger encouraged students to attend a concert, visit a museum, or go to a dance, poetry, or theater performance. She asked her students to then write two paragraphs: one that described a specific psychological study and one that related that study to an artform they experienced. Dr. Munger and her students have been kind enough to share their reflections on artworks from the permanent art collection.

Many students in the class wrote about pieces featured in our fall 2020 From Pandemic to Protests show for one of their culture points and others picked more broadly from our collection as a whole. While there was some overlap in terms of which artworks these students decided to focus on, they each related their piece to a different psychological study, which allowed for a wide range of interpretations. Below we will highlight some of their insights.

Starting out with a campus-wide favorite, Katherine Herrema ’24 reflected on the aesthetic appeal of Yinka Shonibare’s Wind Sculpture (SG) I by connecting it to a 2010 study by Schloss and Palmer that sought to “find out which colors people get the most sensory pleasure from.” Participants were asked to rate how much they liked different color combinations of two overlapping squares “based on pair preference, then harmony, and then focusing on the middle square.” The results of the study showed that “for pair preference and harmony, participants liked when the shade of the middle square and the shade of the background square were the same color… When focusing on the middle square, however, they preferred the two squares to be opposites.” Herrema predicted that “for someone who prefers to focus on pair preference and harmony, Shonibare’s sculpture may not appeal to them… However, if one was to focus on the ‘middle square,’ which in this case I would argue is the blue circle set against the orange background, they would find this sculpture very appealing as the two colors contrast each other and therefore vibrantly stand out.” (Herrema)

Illusory Contours

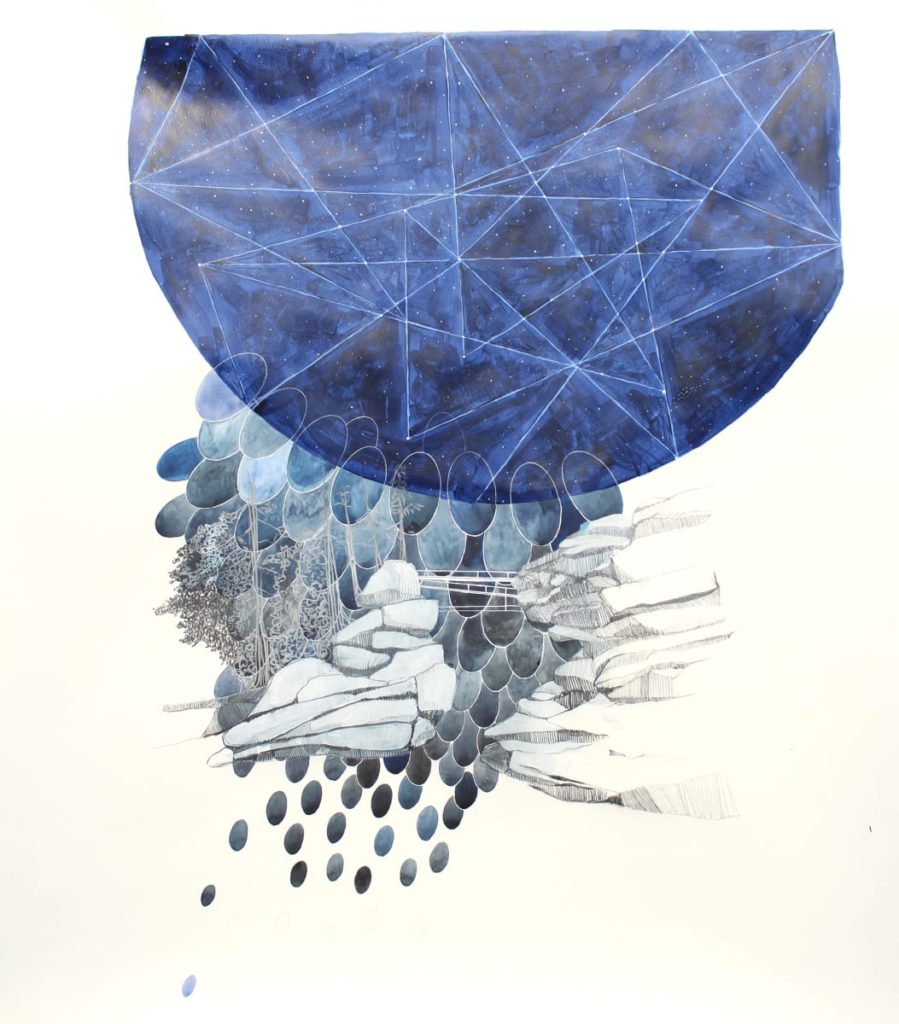

Look Out, 2013 | Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum

Kimaya Gracias ’24 discussed another study about visual perception in relation to Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum’s piece Look Out. In this psychological study, Dr. Hoffman showed an image [see above] to a group of participants that exemplified the phenomenon of illusory contours. While this image is technically only four black circles with triangular cutouts against a white background, to most people there is also a visible white square in the center. Gracias wrote, “Since the edges of the black shapes are identical to the edges of the white square, our minds piece together the existence of the white square through an unconscious inference explanation in order to comprehend the stimulus input, or the pattern.” Gracias noted that in Look Out, “there is a heavy use of overlapping, which creates multiple illusory contours.” She directly connected the painting to Hoffman’s study: “When observing the rocks overlapping the blue oval patterns, our unconscious inference would assume that the blue oval shapes exist behind the rocks just like in Figure 1 where the edges of the square ‘exist’ behind the white triangular cutouts of the black shapes.” (Gracias)

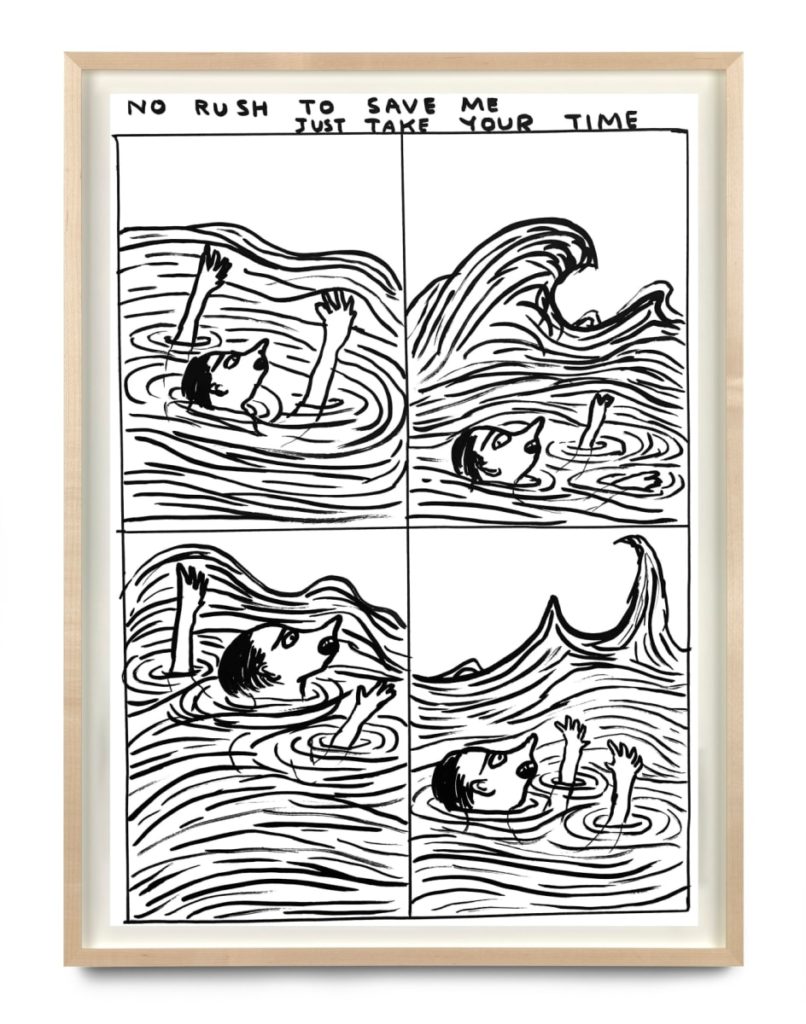

Moving into the first of several studies about the physical expressions of emotion, Anya Neumeister ’24 wrote about David Shrigley’s piece Untitled in comparison to a 2007 study by psychologist Dr. Laura A. Thomas and a group of her colleagues that “sought to examine how different age groups rate morphed facial expressions.” Participants were divided into three groups — children, adolescents, and adults — and each was shown “progressions of facial expressions such as neutral to anger, neutral to fear, and fear to anger.” The study found that “adults were able to better distinguish between slight changes in the emotional expressions as compared to the children and adolescents.” When looking at Shrigley’s piece, Neumeister realized that the subject’s “face slightly changes across the four panels much like the morphed faces used by Thomas and her team.” Because of this similarity, Neumeister wondered, “Would adults find slight changes in emotion within the panels that neither children nor adolescents would observe?” (Neumeister)

Addie Anderson ’24 connected a study about reactions to visuals of anger to Cort Savage’s 2004 piece Everything Everywhere is Already Alright. In this 2007 study by Pichon et al., “the objective was to see if the amygdala, [the part of the brain that experiences emotions], and the premotor cortex, [the part of the brain that plans action], are more activated by dynamic visuals or static visuals of anger.” Participants were shown video clips of angry people as well as still images from these clips depicting the peak moment of anger. The researchers found that “the right amygdala processes anger and becomes much more active with dynamic clips versus static images of anger… The premotor cortex became engaged watching all the visuals, showing that even if the participants were not planning on physically reacting, the premotor cortex was still activated for the potential to react to the stimuli.” Relating this study to Savage’s artwork, Anderson wrote, “The case study found that the premotor cortex is activated in all portrayals of anger, signifying that in the face of anger we are prepared to react. The way in which the amygdala is much more activated by a dynamic visual of anger versus a static one relates to the idea of nullifying the threat — just as the rubber bands in the piece conceal and potentially hide the reality of the threat. In the study, the stillness is only a representation of the anger, waiting to be manifested, just as the black bands are hiding the true nature of the loaded gun inside.” (Anderson)

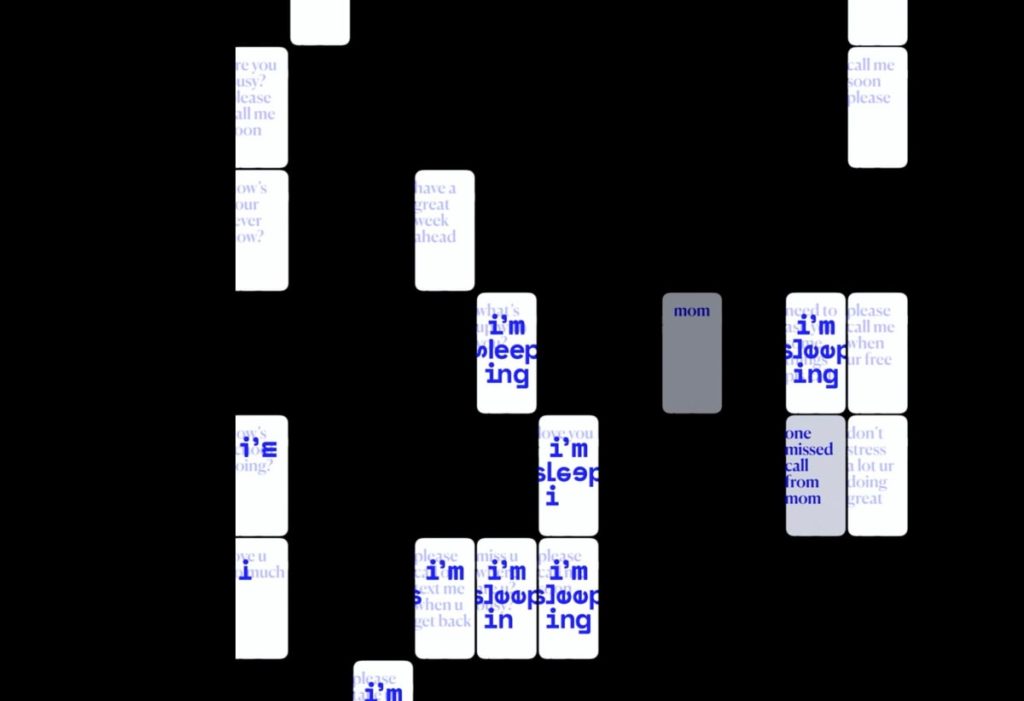

Next, Nora Solomon ’24 found a connection between Katyayani Singh’s piece I’m Sleeping and Russian psychologist Ivan Pavlov’s study from the 1890s on classical conditioning. In this study, Pavlov conditioned dogs to associate the sound of a ringing bell with food. Solomon explained that “before conditioning, dogs did not react to the bell, but they salivated at the sight of food. By the end of the study, the sound of a bell caused the dogs to salivate.” She noted that “the classical conditioning that resulted from the study demonstrates that Pavlov’s hypothesis was correct: reflexes can be altered.” Solomon then connected this study to Singh’s piece based on the way that Singh conditioned herself to react to her mother’s texts: “Whenever her mother would ask questions, her reactions changed from conversational to simply replying with ‘I’m sleeping.’ Singh classically conditioned herself to react to conversational questions with the same response.” (Solomon)

Transitioning from dogs back to humans, Lilly Young ’24 made a fascinating connection between a 1996 study that explored male and female perceptions of sex versus love and Shoshanna Weinberger’s 2015 piece Busted Seams 36DD. In this study, experimenters Harris and Christenfeld asked participants to imagine learning first that their partner was engaging in sexual intercourse with someone else and then that their partner was in love with someone else. In the first scenario, they were asked to rate on a scale of one to five “how likely they thought it was that their partner was in love with that other person.” In the second scenario, they did the same but about the likelihood that their partner was having sex with that other person. The experimenters concluded that “men are statistically more likely to believe sex implies love while women are statically more likely to believe love implies sex.” Young saw a similarity between this study and Weinberger’s artwork, which depicts a “conglomerate of traditionally female body parts and imagery.” She wrote that this piece “shows male obsession with sex; how they often conflate sex with love, and how this can lead to the objectification of women… This pattern connects to the prevalence of erotic imagery in predominantly male oriented culture… and explains why appealing to the male gaze so often leads to the sexualization and objectification of women’s bodies.” (Young)

Lastly, in a connection that is extremely relevant to many issues of today, Olivia Lee ’24 related Bethany Collins’ Dixie’s Land to a 2015 study by Dr. Ellison et al. that examined how humans process music using affective (emotional) and cognitive (logical) judgement. In this study, “the researchers played both major and minor chords, in and out of tune, which were believed to be happy and sad chords, respectively. They then asked participants, using their affective judgment, to determine whether that certain chord was happy or sad.” The results showed that the parietal lobe, which processes sensory information, “was more heavily activated when making a decision about minor/sad music,” showing that the emotions of the participants were more affected by these chords. Lee pointed out that the song “Dixie” ends in a major chord. She wrote, “As shown in the study, most people tend to associate major chords with happiness. However, ‘Dixie’ is reminiscent of an extremely racist time period during the Civil War where white supremacy was especially prevalent.” This piece, according to Lee, works against the study by Ellison et. al when viewed through a historical lens. (Lee)

To learn more about the intersection of the arts and sciences on campus, read this blog post about another one of Dr. Munger’s psychology classes that created an art exhibition called Cognition & the Arts, which will be on display in the Hamilton W. McKay Atrium of the E. Craig Wall Jr. Academic Center through May 21, 2021.

–Alice Berndt ’22