Seen in Storage is a periodic blog post where students, staff, and professors identify some of their favorite works from our permanent art collection. Sometimes clever, sometimes funny, sometimes introspective, and always illuminating, these short posts shine a light on the variety of works that inhabit our beloved basement storage area, when not on view in the galleries or in academic buildings. The permanent art collection provides critical learning experiences to the Davidson community and we encourage you to make an appointment to see these works in person.

This installment of Seen in Storage is brought to you by Helen Sturm ’20.

Josef Albers (German, 1888-1976) was a minimalist painter of the Weimar Bauhaus school in Germany, and later in his career he explored rigid composition in combination with solid planes of three or four colors. His legacy today is in contemporary abstract art where color and form are allowed to speak for themselves without being restricted by subject matter. His own work is connected to fellow German artist Hans Hoffman’s push-pull theory–push-pull describes the use of color to both push the color plane out into space and recede the plane into the surface. Albers utilizes the push-pull technique in many of his pieces to manipulate color and space.

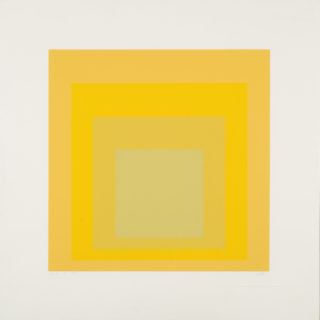

To this day, Josef Albers is one of the most important voices in minimalism and abstract expressionism where non-objectivity is explored in contrast to true realism. His most notable series, Homage to the Square, explores the relationship between color and the form of a square. Davidson College is lucky enough to own a piece from the Homage to the Square series, and it is by far my favorite work in the college’s collection.

In preparation to write this piece, I went down into the archival space in the basement of the Visual Arts Center to comb through all of the paintings, prints, photographs, lithographs, and more that the college has acquired over its existence. As an Art History major, any collection of art meant for human creative consumption is special in my eyes; I get chills every time I walk into a museum or gallery, where I have the privilege of glimpsing the private creative mind of an artist in our physical space. However, the experience of seeing our Albers piece was significant in a different sense—instead of being in a museum institution, however wonderful it may be, I was in a space I felt comfortable in: my own college, in the art department I so love, and in the gallery I am passionate about working in.

I began to comb through the paintings, and my heart raced as I saw a Picasso, a Herb Jackson, and a Dürer– all artists I had studied in Art History classes. However, what caught my eye immediately was a lemon yellow canvas, almost glowing in the dimness of the space, radiating beyond its frame and overtaking my senses completely. I had seen a series of works by Josef Albers at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, and had briefly learned about his German Bauhaus background and his influence at Black Mountain College here in North Carolina. However, I had never resonated so strongly with his minimalism and color theory until I saw the piece in the basement of the Visual Arts Center, the very space where I had discovered my love for Art History. Suddenly, my love for the complexity of painted space as seen with Picasso, Cézanne, and the like was replaced with an appreciation for Albers’ quiet simplicity.

In taking a closer look at this work and letting it fully wash over me, I realized that I had finally reached the point where my inner Art Historian met my inner painter and artist in the plastic arts, which was a combined identity I had never known about before this semester when I took an introductory painting class. Art History had always come fairly easily to me, and I felt comfortable in that department. However, when it came to the studio art requirement for my Art History major, I felt lost and completely adrift. I had never known the sense of freedom and resulting fear an empty canvas– intended for creative expression– gives you. At the beginning of the semester, I was terrified. It took me a good three weeks to trust my instincts and to form my own style, with a lot of coaxing from my professor.

Despite this initial fear, I actually discovered a new aspect of myself that I would not and could not find in the Art History department alone—in painting, I was the creator, not the observer. I took that as an incredible blessing, and started to paint like a madwoman. I grew to love the non-linear process of painting so unlike the predictability of Art History in the classroom. Going back to Albers, in looking at this piece in our collection, I now understand it both as a painter and as a historian—I can look at his handiwork, his manipulation of color, his use of form, and his minimalism and still acknowledge his historical background and his posthumous influence. This is why Albers’ piece radiated out so spectacularly to me that day in the basement—I had finally merged the plastic and historical arts into one complete mindset after two years of studying and hard work. Without going into the basement of the VAC and looking at our collection, I never would have realized my progression into a new type of artist–one that could utilize my hands-on experience as a painter, and also my finely-tuned academic background in Art History. As a junior, my Art History background, my new love for painting, and the beginning of my time in the Van Every & Smith Galleries all came together in the form of a sunny yellow Albers painting.